WHILE RECYCLING WE KEPT COVID -19 AT BAY, STILL SOCIALIZED AND IT WAS FUN

By Daniel Knapp, CEO of Urban Ore, Inc., a Materials Recovery Facility now celebrating its 40th year in Berkeley, California

On my way home from an essential errand today, I got off the I-80 freeway at Gilman in Berkeley to check out the status of Community Conservation Center’s (CCC’s) recycling dropoff, buyback, and materials processing facility. I had a pickup full of cans, bottles, and paper, and in previous days I’d driven by at least twice to no avail as the weight built up and the truck’s handling got more sluggish. Recycling is an “Essential Business” but CCC had been closed to the public. Had they reopened yet?

I turned left onto Second Street, and – great! CCC staff had reopened at least the dropoff function, so I could recycle again. They had made a nice adaptation to the shelter in place order. It was simple: they just opened their two long rolling gates on Second Street and skidded in five-yard bins to plug the gaps. Each bin had a label: “mixed paper,” “cardboard,” “green glass,” and so on through six choices. They had rigged an impromptu dropoff capability that we patrons could access from outside the site.

Inside the fence, CCC was still closed to the public. But staff were busily processing recyclables from commercial and residential curbside service. They were making bales.

I parked next to the three paper bins and put the first of seven or eight heavy bags of paper into the mixed paper. I’m slow because I save the bags for another use, and it takes time to fold them properly.

Meanwhile another patron joined me at the bins, a woman maybe in her sixties. (I’m 80.) We started talking about how nice it was to be able to get rid of our stuff again. I told her I still work for Urban Ore. “I know Urban Ore well,” she said. Meanwhile, a CCC forklift driver had come over, stopped on the other side of the bin row, and was looking at me. He looked like he might want to pull the bin I was dumping into. Then he and I recognized each other. It was none other than Michael Ware, the Supervising Manager at CCC.

Just then a talisman at right appeared. It unlocked the questions of responsibility and what is essential.

Just then a talisman at right appeared. It unlocked the questions of responsibility and what is essential.

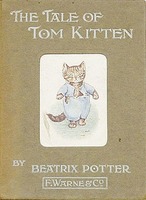

Earlier I had spotted a tiny hardbound children’s book by Beatrix Potter on top of the mixed paper in the bin, but it was too low and far away for me to reach. I had commented about it to the lady and said it was a shame it was in there with the recycling. She looked and immediately walked over to a different CCC employee who was working on a car on the other side of the fence. She told him there was a nice book in the mixed-paper bin. He just kind of fended her off, telling her “not to worry about it.” She rolled her eyes and resumed her outside-the-fence recycling.

Meanwhile, Michael Ware and I had started talking. He got off the forklift to get closer, but we were still the required six feet away.

Then the lady told Mike about the tiny Beatrix Potter book. He looked into the bin, spotted it, then levered himself up with his body draped over the edge like a beach towel. It took him about five seconds to retrieve the book; he was very agile. Back upright on the ground, he held it up and looked at it. I asked if he had a kid he could give it to. He said no, his youngest was sixteen. He reached across the bin, offering it to my recycling companion. She asked me to take it to Urban Ore, so I accepted it and brought it home.

At home I took a closer look at the book. It’s in good condition, first copyrighted in 1907, renewed in 1935. This is the 17th printing. Judging from the coated paper and high-quality print job, it’s maybe 35-40 years old. The title is The Tale of Tom Kitten. The author and illustrator was indeed Beatrix Potter, author of The Tale of Peter Rabbit, and Tom Kitten was the 11th of her 23 tales. The publisher was Frederick Warne & Co. I placed it in the “going to Urban Ore” box we keep by the front door.

I have no idea what it’s worth, but I’ll bet it might fetch a price of between $4 and $8 at our bookstore. Any price over a penny would be a vast multiple of the mixed-paper price if it had been sold as scrap.

Restore the CCC buyback service? When and how is the question.

Then Jeff Belchamber, General Manager of CCC, left what he was doing and walked over to join the conversation. He noted that CCC had decided they could get their dropoff line going again, but were keeping the public out and the Buyback closed based on a directive from the Zero Waste Division.

He said there was some advantage to being closed, because they were able to get necessary maintenance done. I suggested that CCC could tell the City that it is an “Essential Business” for all its functions, including the Buyback that gives people back their nickel deposits, because it provides environmentally superior disposal services compared to wasting. He looked a bit skeptical, and said something about “the politics.” I repeated myself: “But you really are providing a valuable disposal service, and we appreciate it.”

As I spoke I glanced at Mike. He was nodding his head up and down in agreement. He got it! So I suggested to Jeff that he consider asking Mike to help with CCC’s politics, because he understands why all of their functions, not just processing, are essential. From earlier meetings, I thought Mike could do a good job of negotiating with the City to get the Buyback going again.

By this time a fellow in a motorcycle helmet and full motorcycle clothing had joined us outside and was asking Mike when the Buyback would reopen. He said he had a lot of material to bring in. Mike was patiently explaining the closure to him as I closed the awning on my truck canopy.

Jeff walked back to what he had been doing. I got email addresses from Mike and from Denah Bookstein, the lady who rescued the book for Urban Ore, and sent them their own digital copies of The Founders’ Hearts, our book of recycling pioneer stories, as soon as I got home.

That’s my tiny report from the front lines of Berkeley recycling during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic.

# # #